Thank you to everyone who worshiped, gave, decorated, cooked, served, ate, played, and more to make Sunday morning a wonderful celebration.

- Some angels brought gifts

Thank you to everyone who worshiped, gave, decorated, cooked, served, ate, played, and more to make Sunday morning a wonderful celebration.

Isaiah 45:8

Matthew 13:1-9, 31-32

When I was growing up, my family planted morning glory seeds every year along the side of our house: long, green, curly vines, with brilliant blue flowers that open up in the morning. Our morning glories at Newhall Drive in Whitefish Bay Wisconsin grew up happily, twisting around a trellis. Every morning I would go out to check on them, to see how much higher they had grown and to count how many flowers they had.

It’s a sweet memory. So, I decided that I should plant some morning glory seeds for my kids. I can’t say I have a very green thumb, but watching my mother garden for so many years, I know the basics. So I went out to Verrill farm and found some morning glory seeds. Right next to the morning glory seeds at the store were some evening glory seeds, moonflower seeds that bloom at the end of the day. So, I bought some of those too.

I felt really good about my parenting that day. I was not only maintaining a family tradition, I was expanding it! Flowers to count in the morning, and also at night. Vines growing all around the house. Then the seeds just sat there, in their pretty paper packets, on my counter, for a year. A whole year passed without my managing to get any of those seeds into the ground.

Last spring I was determined to do better. My kids were out of diapers! I was ready to conquer the world, or at least, a little gardening. I even looked up the right date to plant the seeds, and put a notification on my electronic calendar. When the date came, and the notification popped up, I went outside with my trowel and spade and seeds and my kids, and we planted those seeds in the best spots I could find. We watered. And we waited. And we waited. And we watered. Nothing seemed to be happening.

You never know what’s going to happen with seeds. Surely the crowds who surrounded Jesus knew that, even better than we do, as they lived closer to the earth. Jesus says to these folks: “Listen! A sower went out to sow. And as he sowed, some seeds fell on the path, and the birds came and ate them up. Other seeds fell on rocky ground … and they sprang up quickly… But when the sun rose … they withered away. Other seeds fell among thorns, and the thorns grew up and choked them. Other seeds fell on good soil and brought forth grain, some a hundred fold, some sixty, some thirty. Let anyone who can hear, listen!

I wonder about the skill of this particular sower. Why sow seeds on a path? Why sow seeds among rocks, or thorns? Why wouldn’t a sower be more careful with her precious seeds, directing them towards only the best soil?

But of course, this is a parable. Jesus even goes on to explain it later on in this chapter. In this parable, Jesus tells us, the seed is the word of the kingdom, the good news of God. This good news is scattered widely among all people, but it does not always grow. Sometimes the seed is stolen from a heart by evil. Sometimes it wilts in the heart, as the result of trouble. Sometimes it its growth is choked in the heart by the cares of the world or the lure of wealth. There are many ways for seeds of the word of the kingdom to die. Still, sometimes, the word reaches a heart that is open and ready, good soil, with good conditions for growth. Someone hears the word and trusts it until it roots down deep within them, bearing fruit and yielding thirty, sixty, or a hundredfold.

I’ve been thinking this week about the seeds that this community scatters. Seeds of the good news, seeds of God’s kingdom. We scatter words of encouragement and wisdom, acts of kindness and service, gifts of presence and prayer, witnesses of justice and love. Our sowing does not always go perfectly. We may occasionally set ourselves too ambitious a planting schedule. We may not always have enough sowers at the right time, in the right place. And many of the seeds we sow, we never know if they grow.

This is simply the way of sowing, Jesus tells us. It’s an act of generosity, with an uncertain outcome. And yet, with all the seeds that die or get drawn away by the wind, some seeds take: and what a magnificent harvest they make.

A magnificent harvest. When someone is comforted by the visits and cards they receive at a difficult time. When young people are empowered to serve, and given a chance to lead. When weary hearts are encouraged with music and prayer, beauty and hope. When our capacity to welcome one another, and to accept ourselves, keeps growing. When our relationships with other faith communities are strengthened. When those who are lonely find companionship. When new people arrive and discover a place that will support and enrich them.

The sowing that we do together is sometimes difficult, but the harvest is enough to take the breath away. God multiplies our efforts, sometimes by thirty, or sixty, or a hundredfold. Like a mustard plant, seeds of God’s good news sometimes find such good soil that they grow and spread like weeds: enormous, persistent, sprouting up everywhere.

As it turns out, the seeds my family planted did not grow very well. The moonflower seeds never even sprouted. The morning glory seeds did sprout, but they never creeped upwards or made flowers.

I’ll plant some seeds again this spring. There’s one thing we can be sure of: without seeds, nothing will grow. I am grateful to be sowing seeds of the kingdom with all of you. And I am grateful for all of the sprouting, and growing, and climbing, and bursting into flower that we get to witness together.

God our Gardener, we give thanks for all that you do. You prepare the soil of our hearts, breaking down rocks, tearing out weeds, sending water and grace. You scatter seeds of good news relentlessly among us, even when we are not ready for them, just in case a root, a sprout, a leaf might grow. You empower us to stretch and bloom, until we can be sowers and seeds ourselves, partners in the work of cultivating your kingdom on earth. Bless us to be a blessing, now and always. Amen.

I Kings 17:8-16

In the book of Kings we learn about the leaders of the Kingdom of Israel. The book begins with stories about the great Kings, David and his son Solomon. It continues with many lesser rulers of a divided kingdom, each seemingly worse than the last. Jeroboam and Reheboam, Abijam and Asa, Nadab and Baasha; Elah and Zimri and Omri; almost all of them regularly do what is evil in the sight of God. But perhaps the worst of all is King Ahab. It is during the reign of this awful Ahab that we meet Elijah: one of the greatest prophets of all time.

Just before our text today begins, the word of God comes to Elijah, predicting a drought. God tells Elijah to go east, and hide himself by the Wadi Cherith. Elijah survives by drinking from the wadi and eating bread and meat delivered by ravens, according to the command of God.

Unfortunately, in time, the wadi dries up. Elijah is no longer provided for. God gives Elijah new instructions: “Go now to Zarephath, which belongs to Sidon, and live there; for I have commanded a widow there to feed you.” Elijah goes to Zarephath and asks a widow for water and food. The woman replies, “I have only a handful of meal in a jar, and a little oil in a jug; I am now gathering a couple of sticks, so that I may go home and prepare it for myself and my son, that we may eat it, and die.”

Elijah is not daunted by the woman’s reply. He says, “Do not be afraid; but prepare some of your food for me, and afterwards make something for yourself and your son. For God says: The jar of meal will not be emptied, and the jug of oil will not fail until the day that the Lord sends rain on the earth.” The woman agrees to do what Elijah asks. And amazingly, she discovers that Elijah is right: her jar and her jug do not fail: her household is well fed.

Recently, I had the opportunity to spend several days with a bunch of church people at a continuing education course on fundraising. We wrestled with big questions about money and faith. We considered new ways to invite people to use their financial resources to support the missions of our organizations. I left totally excited about the role of generosity in our faith lives, and the opportunities we have here at this church to deepen our shared commitments.

It is clear from this passage in the book of Kings that Elijah did not have the opportunity to attend this particular fundraising course. He’s asking for food, instead of money, but it comes down to the same thing. Elijah does just about everything wrong, from a fundraising perspective. He doesn’t get to know the woman at all before inviting her to give. He doesn’t explain what his mission is, why he might be a worthy investment. He doesn’t even truly ask for anything: he just demands what he wants. Worst of all, Elijah doesn’t take no for an answer. When this woman explains that she and her family are literally starving, he still pursues his object aggressively, demanding that she feed him before her own child, and promising that God will not allow her food to run out.

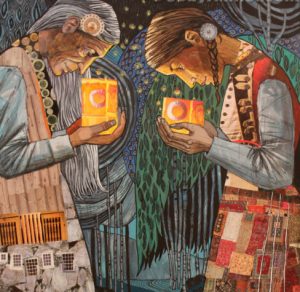

I love the look on the child’s face in the picture of this story. His face says it all. You’re asking us for what? You’re promising us what? I’ve seen that look before. I’ve felt it, on my own face.

I love the look on the child’s face in the picture of this story. His face says it all. You’re asking us for what? You’re promising us what? I’ve seen that look before. I’ve felt it, on my own face.

Strangely, this story ends well. The widow decides to feed Elijah. Meal and oil magically multiply in their containers to satisfy her whole household until the drought is over. What on earth are we supposed to learn from this?

Most of us have a complicated relationship with money, with resources. This relationship is shaped by our history of having too little, or just enough, or more than enough. It’s shaped by the attitudes of our family members and friends, and any faith communities and cultures we have been a part of. Sometimes folks talk about having “common sense” when it comes to money, but in my experience, people have very different ideas about what that common sense should be. There are several radically different philosophies about money floating around in our culture. For example: our American commercial culture tells us to take as much as we can get, and buy the most expensive things we can possibly afford. Commercial culture promises that money can give us pleasure, even happiness, while demonstrating to others how valuable we are. Alternatively, many of us here in New England have been taught to be very cautious with our money. Don’t show what you have; don’t talk about what you have; don’t spend more than you have; make sure you can be responsible for yourself. This Puritan-inspired attitude promises that our money management will prove our morality, preserve our pride, and keep us secure.

Most of us are already confused about money when Jesus comes to crash this party with an entirely different point of view. Jesus tells us that we cannot serve two masters – God and money. Jesus tells a rich young man: “Sell everything you have a give the money to the poor.” Jesus tells us to consider the lilies; not to worry about our basic needs. Nothing that Jesus says could be considered common sense. If we follow Jesus, he won’t make us rich OR responsible. Instead, he tells us something that belies most of our experience. Jesus, and our wider scriptural tradition, tell us: It’s not about the money.

It’s not about the money. How can that be true? Money is great, and helpful, and often necessary. It’s one thing to hear that it’s not about the money in Concord, Massachusetts, where most of us are not planning to lay down and die after our next meal. It’s quite another thing for the widow in our story today. Surely it is about money, about resources, for her.

I struggle with why so many scripture stories lift up the generosity of those in true poverty. I don’t want to romanticize poverty, or spiritualize it. Want is real, and it can be brutal. I do wonder, though, if our ancestors realized what modern research teaches us: it is those with the most limited funds who are statistically the most likely to share them. Those who have the most limited resources are the most likely to be our leaders in generosity.

Why is this? Why are those with the most limited resources the most generous? I wonder if struggling with a lack of money reveals money’s limitations more starkly. Money can do a lot; but in the end, it fails to bring lasting pleasure, true happiness, moral superiority, individual independence, or security. When money is not available, when there is not enough, the truly valuable things are perhaps more obvious: relationship, compassion, community, faith. Money is a means, but not an end. If we make it our end, we are doomed to profound disappointment.

Each year, during our congregational giving appeal, I let you know what I plan to give, and why. I am glad that I am able to continue to give ten percent of my income to this church, dedicating it to God and to the ministry that we are doing here together. I am also working on a better plan for my giving outside of the church: an area for growth.

I should admit that my commitment to the church is not always easy for me. Sometimes I get a little twinge when a pleasure is out of reach of my family. Sometimes I get a little twinge when I think that we should be doing more to ensure our future security. Mostly, I am glad to say, my giving commitment gives me a profound sense of peace and gratitude. I want to keep letting go of false ideas of what money could get me, if I kept it to myself. I want to keep experiencing the power of throwing in my lot with others, of letting the wealth that has come into my hands work for the good of many. I believe in what God is doing here among us, and it moves me to be able to support it. Those quotes, those dreams we heard at the beginning of the service – they are worth the world to me.

Ultimately, scriptures teach us, nothing actually belongs to us individually. Ownership is an illusion. We can only be stewards for the wealth that comes from God and belongs to all God’s people, all of God’s creation. The amazing thing is, that the more we learn to share what we have with one another, the more it grows. Instead of fear and scarcity, as we give and connect we discover abundance: abundant resources, abundant love, abundant possibility. As our hands open towards one another, loaves and fishes multiply, and meal and oil appear out of thin air, through the mysterious and marvelous grace of God.

Dear God, money makes us anxious and afraid and enthralled and protective. It pushes our buttons, and we get all wrapped up in it, instead of being focused on you. Whatever numbers are in our bank accounts, help us to breathe deeply, day by day, shedding fear and shame and pride. Teach us that our true value and security come from you. Teach us how to share what we are able and called to share with glad and generous hearts, that we might relieve the wants of others, free ourselves of every burden, and participate in your miraculous multiplication. Amen.

I wonder if you a ll could help me this morning think of ways that our church welcomes people. When people arrive at our church doors on a Sunday morning, what are some of the things we do to help them feel welcome? (Ideas included: provide greeters, say “good morning!,” shake hands, provide an elevator.)

ll could help me this morning think of ways that our church welcomes people. When people arrive at our church doors on a Sunday morning, what are some of the things we do to help them feel welcome? (Ideas included: provide greeters, say “good morning!,” shake hands, provide an elevator.)

As folks come into the sanctuary and participate in worship, are there things we do to make people comfortable, or to make sure they can participate? (Ideas included: chairs to sit on, space for wheelchairs, large-print bulletins, hearing assist devices, visual worship guides, headphones to block out noise, toys to keep our hands busy if that helps us, activity stations.)

Do we do anything outside our building to help people feel welcome? (Ideas included: Welcome Garden, special parking spaces, rainbow flags, Black Lives Matter & Yes on 3 signs)

This church does a lot to welcome people, and we keep trying to make our welcoming muscles stronger. We want everyone to feel that they have a spiritual home; that they’re not alone.

Our scripture story today is about someone who felt alone, and afraid, and who didn’t have a home. Naomi and her family are refugees, people who are forced to leave their homeland to survive, like so many people in our world today. They are able to travel to a new place, and they find the food they need. But then, Naomi’s husband and sons die. The only people who are left in Naomi’s family are her, and her two daughters-in-law. Naomi knows that she does not have what she needs to keep her daughters-in-law safe and healthy. So, she tells them to go back to the homes they had grown up in. She tells them to let her go, alone, back to the place where she grew up: Bethlehem of Judah.

Naomi is trying to be practical, and she is trying to be generous. She’s worried that she doesn’t have much to offer anyone else. But here is the really amazing part of this story. Ruth decides that being together with this person that she loves is more important than anything else. She decides that whatever is going to happen next, it will be better if she and Naomi face it together. So Ruth tells Naomi: “Where you go, I will go; where you stay, I will stay. Your people shall be my people, and your God my God… Not even death will part me from you.”

Ruth goes with Naomi, and together they help one another make a new life, and a new home.

This season at church we are thinking about how we can be more like Ruth. Ruth gives the gift of help and companionship along the way. She goes with Naomi, even though it means traveling to a place she has never been before. Ruth brings the gifts that God gives her out into an unfamiliar world.

How can we be like Ruth? If we’ve already built strong welcoming muscles, how can we strengthen our muscles to bring forth the love of God beyond our walls and into the world? A few ideas:

How else can we be like Ruth? What are some other ways we can bring forth God’s love and justice into the world? (Folks reflected on this and recorded their ideas on hearts to share).

Dear God, open our hearts to follow in the ways of our ancestor Ruth, Going, and staying, and living, and dying, together with all your children. Amen.

Revelation 21:1-6a

In the book of Revelation, John of Patmos recounts what God has unveiled before him in visions and in voices. One of the most famous passages from John’s writings is the one we hear today: a vision of a new heaven and a new earth. In this new reality, John writes, God is at home among the people. There is no mourning or crying or pain anymore. Even death has ceased to exist. All things are made new, and God says, “I am the Alpha and the Omega, the beginning and the end.”

Is this what is in store for us? I have to say, I hope so. It is one of the more beautiful passages in scripture about what might come next.

People often turn to the church, and to scripture, when they are wondering about the great mysteries of death and dying, heaven and eternity. And it’s not only adults. In confirmation class, this is always one of the most popular topics. Children like to ask questions about it, too. We all want to know what will happen to us in the great beyond. We are curious, also, about what will happen, and what has happened, to those we love.

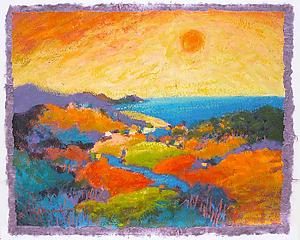

These questions are particularly prominent in this time of year. I often think of this as the dying time. Leaves are falling and plants are sinking back towards the earth. People often find their way back to the earth, too, following the tidal movement of the season. This is a time when the barrier between the living and the dead feels thin, as we celebrate All Hallows Eve and The Day of the Dead and All Saints and All Souls. Today we’ll continue our series of visual sermons, focusing on what lies beyond.

When we think of the church’s view of what lies beyond, I am afraid that too many of us think first of the Last Judgement, an idea based around passages from the Gospel of Matthew and Luke. Here is Michelangelo’s depiction of God judging the people, sending some to heaven and others to hell. The idea is attractive because it is so concrete. Do good and end up somewhere good. Do bad and end up somewhere bad. Trust that God will mete out justice in the end to anyone who treats you badly. But what does this theology say about God?

When we think of the church’s view of what lies beyond, I am afraid that too many of us think first of the Last Judgement, an idea based around passages from the Gospel of Matthew and Luke. Here is Michelangelo’s depiction of God judging the people, sending some to heaven and others to hell. The idea is attractive because it is so concrete. Do good and end up somewhere good. Do bad and end up somewhere bad. Trust that God will mete out justice in the end to anyone who treats you badly. But what does this theology say about God?

Looking at the upper left hand part of this picture, you can see the people who are being elevated into heaven. This is the good news part of the picture. Everyone should look happy. But even though they are safe in the clouds, surrounded by light, they don’t seem to be enjoying themselves. Instead, they’re staring to the side in apprehension.

Maybe that’s because, right next to them, they see this: an absurdly muscular God making a threatening gesture, sending lots of other people down below…to flaming torment. I find nothing here that could be the will of a loving God.

Our scriptures and our church traditions were inspired by God, but formed and recorded by humans. Therefore, when an idea like the Last Judgement fails the test of demonstrating God’s love, it is best we look elsewhere for guidance. Thankfully, we have many other scripture passages that suggest an entirely different reality after death.

In the Gospel of John (Ch 14), Jesus is saying goodbye to his disciples. He tells them: ‘Do not let your hearts be troubled. Trust in God; trust also in me. In my Father’s house there are many dwelling-places. I will go and prepare a place for you; I will come again and will take you to myself,so that where I am, there you may be also.”

In the book of Romans (8:38-39) Paul writes: “I am convinced that neither death, nor life, nor angels, nor rulers, nor things present, nor things to come, nor powers, nor height, nor depth, nor anything else in all creation, will be able to separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord.”

Throughout the scriptures, we learn that God loves us; that we belong to God; that we are made and remade in God’s image; that we are a precious part of God’s holy creation. It is fitting, then, that after our human lives are over, we would all return more deeply, more fully, to make our home in God, who is our beginning and our end.

Throughout the scriptures, we learn that God loves us; that we belong to God; that we are made and remade in God’s image; that we are a precious part of God’s holy creation. It is fitting, then, that after our human lives are over, we would all return more deeply, more fully, to make our home in God, who is our beginning and our end.

This leaves, still, the question of saints, and souls. Where are those we have loved and honored? How can we visualize the great cloud of witnesses who are hovering around us?

Probably you have seen pictures like this: saints in gold, carefully posed. Most of our images of saints in the west are like this: white people, in fancy clothes, often with halos, lined up in orderly ways, as if for a photo opp. The saints knew how to stand in a line, apparently. These images are beautiful, but limited. Thankfully, some artists have tried to help us expand the way we imagine the saints.

Probably you have seen pictures like this: saints in gold, carefully posed. Most of our images of saints in the west are like this: white people, in fancy clothes, often with halos, lined up in orderly ways, as if for a photo opp. The saints knew how to stand in a line, apparently. These images are beautiful, but limited. Thankfully, some artists have tried to help us expand the way we imagine the saints.

Some of my favorite saint images are from the Catholic Cathedral in LA, where tapestries depict saints of all ages and cultures and skin tones, both famous and unknown, including children. These images help remind us that there have been holy people all around the world, and in every social location.

Some of my favorite saint images are from the Catholic Cathedral in LA, where tapestries depict saints of all ages and cultures and skin tones, both famous and unknown, including children. These images help remind us that there have been holy people all around the world, and in every social location.

Another favorite is the work of Robert Lentz. He who writes icons and creates images that depict those who have not normally been recognized as saints: the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and Caesar Chavez,and Eve, mother of us all. Brother Lentz also depicts those who have been formally recognized as saints by the Catholic Church, but whom we may not be as familiar with, or choose to feature, including ancient Armenian saints Polyeuct and Nearchus, and the recently sainted Josephine Bahkita., from the Sudan.

While I love to be inspired to by the images and stories of courageous people who have changed the world, I have to admit that the most powerful saints and souls in my life are the ones that I have known, and cared for. Each of us have our own group of those we remember tenderly; here are a few images of those who many of us remember from our shared life here.

Beautiful, aren’t they?

Many of us experience fear or anxiety in thinking about death. All of us experience grief at the death of those we love. As we stand on this side of the mystery, God offers us at least two gifts. First, the promise that she is not only our beginning, but also our end, that she will provide a loving home for us. And also, that we will have with us in that home each person who has made our time on earth better: legions of saints and souls, a cloud of witnesses, also safely in God’s care, and accompanying us into eternity. Thanks be to God.

Job 38:1-11

A message from the Rev. Polly Jenkins Man, October 21, 2018

God answers Job, yet I doubt if it’s what he wanted to hear. Not after all he had suffered, all he had lost…children, servants, livestock, his home and his health. He simply wanted God to tell him why. Why am I in this situation? What have I done, or not done? He must have been terribly disappointed confused, even terrified. Nonetheless, if we put aside poor old Job for just a moment, and look simply at the language: the imagery and the metaphors in God’s answer to Job; it is a magnificent poem, one of the most imaginative and beautiful literary pieces in all of scripture. In just those 11 verses which Keith read, we discover God as an architect and a builder; as a mother and a midwife; a nurse, even a hydrologist.

And after these, there are four chapters full of the same: God is a falconer, an astrophysicist, farmer and shepherd; hunter, a potter , and much more. When Hannah asked if I wanted to preach this fall and gave me a few choices for dates I looked at the lectionary and discovered that the passage from Job was indicated for this morning. So there was no question that today would be the day. Job, Chapters 38-41 is close to number one on my playlist of Bible passages. I urge you to read it, the language is stunning. I was actually really tempted to let the whole poem be my sermon.

But Job led me in another direction.

Who is Job?

Job is a homeless refugee in a crowded, filthy detention facility, whose village has been reduced to rubble in Syria.. Job is a Rohingyan mother running from the soldiers of her own country, forced to leave all her belongings behind. Job is the two year old. Mexican child separated from her parents and held in behind a chain link fence, terrified and alone. Job is a person with AIDS, covered with sores. Job is the Puerto Rican grandfather who saw the neighborhood where he has lived all his life completely destroyed in just a few minutes by Hurricane Maria. Job is the woman who was sexually assaulted as a teenager by an entitled prep school boy, who had the courage to speak out and was then summarily dismissed by the agents of patriarchy, power and politics.

Job is all of these and everyone who has ever suffered loss, abuse, discrimination, homelessness, crippling illness or war.

“There once was a man in the land of Uz whose name was Job. That man was blameless and upright, one who feared God and turned away from evil.”

So the story of Job begins, as a folk tale. One day when all the heavenly beings present themselves before God, Satan shows up after walking to and fro upon the earth. God asks him “Have you observed my servant Job, blameless and righteous?”; and in the course of their following conversation, God and Satan make a bet using Job as their pawn. Satan wagers that Job will turn away from God if the good life, his family, wealth and health all are taken away.

Which is precisely what happens: all is lost and Job, naked, his body covered with sores, goes out and sits on a pile of ashes.

He then begins to question: “Why did I not die at birth, come forth from the womb and expire? Why is light given to one who is in misery and life to the bitter in soul?” His friends arrive, one by one, each ready to figure out why he’s in such a sorry state. “You must have sinned, they tell him, and that’s why God punished you.” They’ve simply come to help him figure out what he did or didn’t do. “Think now,” one says, “Who that was innocent ever perished?”

They really don’t get it, and it’s really because they’re asking the wrong questions. That’s not Job’s question. He knows he is innocent; he hasn’t abandoned his faith or cursed God. After all, according to the folk story, that’s precisely why God chose him for the wager with Satan. Rather, Job’s question is as ancient as humankind and as timely as today: “Why do bad things happen to good people?” That’s what Job wants to know.

Why are thousands sick and dying in crowded refugee camps and detention centers? Why are villages burned, women raped and men murdered because of their ethnicity? Why are babies and children separated from their mothers and fathers? Why are so many innocent young men in prison?

I don’t believe God has anything to do with it. Fear, racism, religion, wealth and power…and much more… these are all human, not God caused.

And Job believes that God can and will explain it. He doesn’t let up, but keeps knocking, as it were, on God’s door. Then, finally God speaks:

“The Lord answered Job out of the whirlwind: Who is this that darkens counsel without knowledge? Gird up your loins like a man.” A voice like a thunder clap:

“Where were you when I laid the foundations of the earth? Surely you know…Or who shut in the sea with doors?”

That’s not an answer. It’s just a series of rhetorical questions. To which both God and Job already know all the answers. And God definitely doesn’t tell Job “Oh, it’s all because I made a bet with Satan. And I won!”

In the long run, though, if anyone won, it was Job. Because he persisted, never gave up, never lost faith. Job never cursed God. He never gave up believing that God would hear him. And God did, although not as he had expected

He never did get an answer to his question: “Why do bad things happen to good people?” And that’s because it seems to me that the story of Job in its entirety is an answer to yet another question. “What is it in the human spirit that never gives up despite the very worst that happens?

What is it, for example, that persuaded the Lost Boys of Sudan to walk across a continent after they were displaced or orphaned; seeking a new life.

How is it that so many women survive horrific sexual abuse to become strong national advocates for change?

What was there in John McCain, a prisoner of war for five years, that helped him survive brutal torture to become one of the greatest statesmen of our time.

What is it that makes a Mexican family try over and over again to get across the border until finally they do find asylum?

These are all Job’s people. That persist against all the odds. That tap into an indomitable faith and keep saying “yes’ to life. That survive and thrive after the worst the world has to offer.

They keep on keeping on.

You know at least one person like that, right? Who is resilient and refuses to let life beat her down. At the same time, I suspect we all know folks who have been crushed by life through no fault of their own. What about them? How do they keep going?

That’s where we come in, since through our faith we are called by the Spirit: to visit the sick and comfort those in prison, provide food and shelter and welcome to the stranger.

To help heal a wounded heart, and speak out against injustice and inequality.

In the end, God’s answer to Job turns out to be a question for us who live in this hurting world; will we do our part to make it a little bit better?

Mark 10:35-45

The disciples still don’t get it.

If you were here a few weeks ago, as we were working our way through the gospel of Mark, you may recall that the disciples spend time arguing with each other about who is the greatest. Jesus tries to explain: Whoever wants to be first must be last of all and servant of all.

Later, the disciple John tries to get praise from Jesus by reporting that he tried to stop another healer from healing in Jesus’ name. Jesus tries to explain: anyone who is not against us is for us; there is no hierarchy among those doing good.

As the Gospel continues from there, the disciples try to keep children from coming to Jesus. Jesus tries to explain: it is to such as these that the Kingdom of God belongs: not to rich or important adults, but especially to children.

But the disciples still don’t get it. They are still struggling to understand that with God, social hierarchies are tipped over and turned inside out; no one is left out and everyone is invited in, everyone is precious.

Now James and John come to Jesus saying, “Teacher, we want you to do for us whatever we ask of you.”

What a set-up. Jesus is no fool. He asks: “What is it you want me to do for you?”

James and John say, “Grant us to sit, one at your right hand and one at your left, in your glory.” In other words, promise us the best seats in heaven.

And Jesus tries to explain — again. “You know that among others, those they recognize as their rulers lord it over them, and their great ones are tyrants over them. But it is not so among you; whoever wishes to become great among you must be your servant, and whoever wishes to be first among you must be slave of all. For the son of man came not to be served but to serve, and to give his life for many.”

The realm of God doesn’t have a throne room, apparently, or a long rectangular banquet table, in which chairs are arranged in order of precedence. Greatness comes not through placement, or abuse of power, but through service, and sacrifice, and generosity.

This month I am using images to help us reflect on scripture. Last Sunday, we used images to explore who God is and how God works, according to the second story of Creation.

Today we turn our attention to Jesus. How do we imagine this Jesus, this Son of Man — someone who is glorious, highly acclaimed, and yet preaches and lives a way of service?

Have you seen this Jesus? He is #1 on the google Jesus search. Friends, was the historical Jesus a pale skinned, blue-eyed man? No! Jesus probably looked something more like this: darker hair, darker eyes, darker skin, different features; a Jewish man from the ancient near east without a pervasive pastel glow.

Jesus probably looked something more like this: darker hair, darker eyes, darker skin, different features; a Jewish man from the ancient near east without a pervasive pastel glow.

But we needn’t be limited to images of the historical Jesus. It’s natural for people in all times and places to imagine that Jesus looks like us. Jesus is the human one, a way that God gets close to us, we want to see ourselves in him. So, if you look hard, you can find images of an Asian Jesus, a Native American Jesus, a Jesus of African origins.

It is comforting to imagine Jesus looking like us, like our family members, like our friends: familiar, relatable. It’s also important as we imagine Jesus into all sorts of different skin tones and cultural identities and social locations that we notice how these identities impact how we understand the image and story of Jesus; and how the image and story of Jesus impacts how we understand people with these identities.

What kinds of people do we imagine in the Holy Family, and how does that impact which families we imagine as holy?

How do we portray a powerful Jesus? What does that say about which humans have power, and the kind of power that Jesus has?

Which kinds of human figures might best express the terror and tragedy of the crucifixion, as we experience it in our world today?

Images of Jesus are powerful: powerful in reflecting our identities and beliefs, and also powerful in confirming or challenging them.

When the statue on the right, a female figure on a cross titled “Christa” was first displayed in the 1980s in St. John the Divine Cathedral in NYC, the suffraganbishop of the Episcopal Diocese of New York called the statue “theologically and historically indefensible” and ordered the artist, Edwina Sandys, to take it away. But why was it so very troubling, to see a female figure on a cross, when we have imagined Jesus in so many ways that do not match his historical identity?

What should Jesus look like if Jesus is for all of us? The artist Janet McKenzie tried to answer this question when she created this image, called Jesus of the Peoples: a Jesus who is perhaps between cultures, even between genders.

But maybe it’s best if we have lots of different images for Jesus: familiar and unfamiliar, comforting and challenging. Just as we use many names for God, using many images for Jesus may be more accurate, and more helpful to our faith, than using only one.

Using many images for Jesus is even more important because most of us still have something like that first image embedded in our subconscious. We’ve just seen this white Jesus so often that without good reminders we may fall back on the assumption that Jesus is white. We may cling to this Jesus, especially those of us who are white ourselves, just as the disciples clung to their ideas of hierarchy; hoping that our cultural biases and desire for precedence need never be disturbed by God.

I think it will do us all good to seek out and spend time with images of Jesus that are not white. As we meditate, all of us, on diverse images of Christ, these Images can serve as icons, as arrows pointing towards the holy human one who is so far beyond our limited understanding, and who calls us to transform our relationships with the humans around us of all skin colors and cultures and social locations.

We, like the first disciples, will probably never truly get it: that the last shall be first, and the first shall be last, and that the kingdom of God belongs to the least of these. But we will at least discover more about this Jesus who does not rule as a tyrant over us; this Christ invites all people into communion in his church, and around his table. May it be so.

In the book of Genesis there are two creation stories. In the first story, God cries out into the chaos and Creation responds: light divides from dark, land from the waters, sky from earth, day from night.A beautifully constructed order emerges over six days. On the seventh day, God rests.

It is a beautiful story. There is another story, too.The second story of creation in Genesis has something entirely different to tell us.

When you think of the second story of creation in the book of Genesis, you may think of Michelangelo’s beautifully muscled, bearded God, creating a beautifully muscled, graceful Adam with only a gesture. Or you may think of the Tree of life, the snake, the forbidden fruit, and the end of Eden. But that’s not the part of the story that I’m interested in today. I invite you to notice something different about this creation story.

This story begins with dust. There is nothing on the earth but dust, dirt, earth. Earth and water. And the first thing God does is form that earth into a human form, and fill that human form with breath, with life.

There is so much water flowing around that dust, that dirt, that earth, that I wonder if the forming of that first human body may have looked a bit like a potter working with clay. If you’ve ever worked with clay before, imagine that feeling of clay on your hands, on everything you touch: maybe God’s hands were like that.

God formed a human out of wet earth. It must have made a mess.

But that didn’t seem like enough, somehow, something felt unfinished. So God planted a garden in Eden, in the east. God planted every tree that was beautiful, and bore good fruit. And now the human had a home, and the human had a purpose:a garden to tend and to till.

But that didn’t feel like enough somehow,something still seemed unfinished. God said: It is not good that the human should be alone; I will make this human a helper as a partner.

Strangely enough, God decided that the best way to find a helper and partner for the human was to make animals out of the earth: animals of the field and birds of the air. How long did all this making take? The story doesn’t tell us. Imagine all that wet earth, the shaping of each animal of the field and bird of the air. It could have taken weeks, or years.

However long it took, the human enjoyed the process, watching God form these magnificent creatures. The human delighted in giving the animals names. Naming has been a human gift from the beginning. But the human did not find among these animals any that could truly be a partner.

So God tried again. God caused the human to sleep deeply, and removed a rib from the human’s body, and closed the body. And with the rib, God made another human: Bone of bone, flesh of flesh, an equal helper: a true partner.

In most of the artwork I can find, the second human is lifted whole out of the side of the first, but that’s not what the text says. This making must have been messy, too: Blood and bone, instead of dirt and clay.

Let’s take a moment to let this really sink in: that God could have such a hands-on approach to the making of human bodies, to the making of all creation.

Surely God must have a special tender care then for each physical part of this creation. God must care very much what happens to the special holy gift of each of our bodies. We are a precious gift, each one of us — handmade by the best.

God must be intuitive and experimental, too:to understand that we get lonely, and to know, once it had been tried, that a rhinoceros was not enough. To work so hard, and try so many times, before finally making a helper who is a true partner.

This God, who loves our bodies, seems to be figuring it all out right alongside us: trying to meet creation’s needs again and again, getting it wrong sometimes, and getting dirty in the process.

The God in the Second creation story does not have it all figured out. This God does not direct things from afar through voice or strength of will or superior muscle tone.

This God is hands on, and works with clay.

God, when I am helpless or hopeless, teach me that I am precious. Work with the messy and holy material in and around me for as long as it takes until we can make things better. Find me true partners so I will not be alone. Amen.

Sunday Fellowship is back! With our 35th anniversary celebrations behind us and the renovations complete, we’re ready to try some new things.

Our focus this year is on discipleship and what followers of Jesus actually do to become more like him. Over the next several weeks and months, SF will explore different Christian practices like peace-making, justice-seeking, communion, baptism, sharing our spiritual gifts, sabbath rest and more.

So far we’ve already introduced a new way of “passing the peace” using white silk scarves. We talked about what Jesus might have meant when he told his disciples before he died: “Peace I leave with you; my peace I give to you. I do not give to you as the world gives.” Check out these videos that helped us come up with the idea of peace scarves and reminded us of the transformational power of practicing peace: https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=22&v=QgbFTBJb3xY and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jvOllDWTnyY.

Sunday Fellowship’s next gathering will be on October 14 at 4 p.m. Come join us as we begin to explore our spiritual gifts and John Swinton’s view that “within the body of Christ, every body has a place, and every body is recognized as a disciple with a call from Jesus and a vocation that the church needs if it is truly to be the body of Jesus.”

Proverbs 31:10-31

Proverbs 31:10-31

Mark 9:30-37

I wonder sometimes how Jesus chose his disciples.

Jesus was kind of a big deal. He was a fascinating speaker, an extraordinarily gifted healer. His presence communicated charisma and compassion. There were plenty of wandering reforming rabbis in the ancient near east, but Jesus got some of the biggest crowds.

Jesus could have chosen anyone to be part of the twelve. The most highly educated, the wealthiest, even the wisest. Instead, he chose a bunch of tradespeople. They rarely understand what he’s saying. They are too afraid to ask questions when things get real. And in in today’s gospel, they spend their travel time arguing about which one of them is the greatest.

Apparently, Jesus hears some of the conversation that his disciples have. When they get to Capernaum, he asks them, “What were you arguing about on the way?” But the disciples won’t own up to what they’ve been doing. I imagine them avoiding his gaze and glaring at one another, while Jesus looks on with equal parts love and exasperation.

Jesus calls the twelve to come over have a talk with him. He tells them, “Whoever wants to be first must be last of all and servant of all.” He invites over a small child, who has probably been watching them from a distance. Jesus takes the child in his arms and says, “Whoever welcomes one such child in my name welcomes me, and whoever welcomes me welcomes not me but the one who sent me.”

It’s fun to laugh at the disciples, but let’s be honest; all of us know how to play the game “who is the greatest.” It’s a game we learn early on. Who will be picked first when the T-Ball teams are formed? Who will rank first on the GPA list? Who is the funniest, the wealthiest, the most beautiful, the most popular?

We start ranking one another early in life, and the lists just keep going as we grow up. We compare ourselves to family members and coworkers and friends and people on the news and even the random person we see on the street. Is that person or more or less attractive than me? Is that person more or less important than me? Is that person more or less loved than me? How do we compare? Who is coming out ahead?

Comparisons are famously odious, and yet we compete and compare over and over and over again. Even the bible has passages that give lists of qualifications to live up to. The most egregious is found in the book of Proverbs, a passage detailing the attributes of a capable wife. Apparently, the best of wives must achieve at least 25 awe-inspiring tasks and personal virtues in order to earn the praise of her husband, and prove her love of God. If only it were possible. But can a woman rise before dawn, fill her days with labor for others and words of wisdom, stay up all night, and not collapse in exhaustion? Is this really a good yardstick for a human being?

What’s more, it seems suspicious that wives are the only ones chosen for such detailed job descriptions. What about husbands? Single people? Scripture writers?

Our human desire to rank ourselves and one another is damaging: and not only to our own individual senses of worth. Ranking is a building block of racism, classism, homophobia, and other forms of prejudice and oppression. We invent classification systems whole groups of people in which some people are more important, and some people are less important, and some people are not even really considered human.

It is this basic instinct that leads us to have different rules for different people. Who deserves citizenship? Who deserves clean air, or a park in their neighborhood? Who is allowed to speak in the board room? Who can express anger on the tennis court? Who may seek justice for a crime committed against them? Who is held accountable for their actions? More often than not, it depends on how we rank on the list.

Ranking hurts everyone. Most profoundly it hurts people perceived to be on the bottom, whose lives and health are at risk. Rank also hurts people on the top, who live in safety while their souls grow twisted. Wherever we end up on society’s list of power players, ranking gets inside our hearts, and denies us our ability to see ourselves and one another as we truly are.

But Jesus hears us as we keep going on and on about who is the greatest. He calls us over, invites us to have a good talk. It doesn’t have to be this way, Jesus tells us. Follow me to freedom.

Choose to be last instead of first, Jesus says — if you have the choice. Choose to be servants instead of masters. Shake up the pile, scramble the list, align yourself with the disempowered, and welcome even children: those little ones who make messes, and ask inconvenient questions, and offer hugs, sometimes to strangers.

Jesus’ message is even more powerful because we know what he chose. Jesus aligned himself with the poor, and with prostitutes, and with tax collectors, and with sinners of every kind. Jesus chose to live a life that would demote him to the very bottom of the list, and he paid for it.

I invite you, as you are comfortable, to close your eyes for a moment….take some deep breaths… and imagine a person who has, to the best of their ability, known who you really are. Loved you, just as you are. Treasured you. Remember the feeling that you have gotten from being known and love and treasured. Make room to receive that feeling, accept that feeling, as if they were right here with you.

Now imagine that this is how God feels about you. This is how God knows, and loves, and treasures you. Despite all your mistakes and limitations, God is head-over-heels in love with you.

Now imagine that this is how God feels about the person sitting next to you. God knows, and loves, and treasures them. God feels this way about that person right next to you; and the person next to them; and the person next to them. God feels this way about everyone in this room; and everyone we have ever known; and everyone they have ever known. God feels this way about people in every time, and every place: knowing all of us, loving all of us, treasuring all of us.

We are, each and everyone one of us, God’s beloved children. This is the most true thing we can know about ourselves, or anyone else. In the end, all the ranking systems and stacking hierarchies crumble to nothing in the face of this enormous truth. All we need to do is breathe, and let that love in.

Please pray with me.

God, relieve me of the cruel thoughts I tell myself, as I measure myself against the world. God, relieve me of the cruel thoughts I have of others, as I measure them. Free me instead to experience the world as you experience it: Full of beautiful imperfect creations that you know, love, and treasure. Amen.