Today is Covenanting Sunday, when we start up new programs, when we call back those who vacation from church in the summer, when we remember our Covenant to keep one another company along the journey of our faith. As we gather together today, we hear a piece of scripture from the gospel of Matthew that comes from a whole section in which Jesus gives instructions to his followers about how to live in community. There’s all kinds of great advice in this section for us to consider, like: Treat one another as children of God; avoid doing what would cause other people to stumble; care for those who are most vulnerable; and forgive one another without limit. Great advice, if sometimes difficult to follow.

In among all this great advice is one much more specific piece of instruction, which we heard this morning. It explains what to do if someone has sinned against you. This piece of scripture is often repeated to help us figure out how to deal with conflict as Christians. If someone sins against you, go directly to the person who caused your injury. Talk with them. If, after a frank discussion, the person will not listen, then take someone with you, and try again. If the issue is still not resolved, bring it to the church as a whole. And if even consultation with the whole church will not resolve the conflic, then the person must be separated from you, and from the church, become an outsider.

It’s remarkable just how good Jesus’ advice is. He told us two thousand years ago not to triangulate; and we’re still trying to learn that lesson. He knew that people can’t solve conflicts without talking directly and honestly with one another. The rest of his advice is good, too. When we can’t solve a problem one-on-one, bringing in some helpers makes sense. And he is wise to point out that sometimes we still have to set a limit and fundamentally change our relationship with someone because of the way they have treated us. Jesus knows what he’s talking about.

But here’s the rub: Jesus’ instructions tell us what to do if someone sins against us. But there’s at least two sides to every story. When we get into a conflict with someone, how do we really know who is sinning? Or who is sinning more? When push comes to shove, which side of the argument should the church be on?

500 years ago, the church founded in the name of Jesus Christ got into a fight. A massive, no-holds-barred, down-and-dirty brawl. It started simply enough: with disagreements about theology and church practice. For years, across Europe, folks raised concerns about the selling of God’s forgiveness through the sale of indulgences. People questioned the hierarchy of the church, the system of priests, bishops, and pope. People debated the relative importance of scripture and tradition as a source of authority in the church. People argued about the liturgy and the sacraments, and whether ordinary people had enough access to holy things.

These issues are important. But as with most conflicts, this one became explosive not so much because of the issues themselves, but because of how the issues were dealt with. Take, for example, the first prominent instance of Reformation thinking, back in the 15th century.

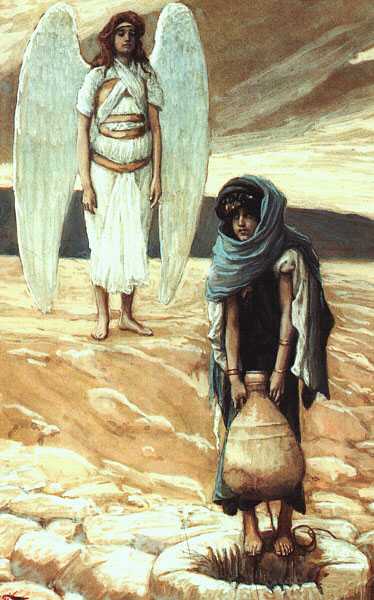

An Oxford seminary professor named John Wycliffe produced writings that criticized the church extensively. His ideas inspired Jan Hus, a priest and University dean in Prague, who proceeded to preach regularly on the failings of the church and its leadership. If you read up on them, you may find that you agree with their ideas; or not. What I want to highlight is not so much what they said, but how the church responded to them. After their Bishops failed to reign them in, they were both declared heretics at the churchwide Council of Constance. Then, Jan Hus, who had been guaranteed safe conduct to the Council, was burned at the stake. And John Wycliffe, who had already died, was exhumed in order to be burned as well. His writings were also destroyed.

As you can imagine, church reformers did not respond well to these actions. Leaders of Bohemia and Moravia sent a letter to the Council at Constance denouncing the execution of Jan Hus. In response, a Council leader sent letters back threatening to drown all followers of Hus and Wycliffe. Violence broke out across the region, leading to 15 years of war between the people in what is now the Czech republic and their rulers, who were loyal to the church institution.

This was just the beginning. A prelude to the conflict of the Reformation itself. Because, it seems, no one learned a lesson from those events. The church continued with its existing policies. In fact, Pope Sixtus IV expanded the sale of indulgences, so they could be applied not only to the living, but also to the dead. Meanwhile, church reformers were energized by the ideas of both men, and by Wycliffe’s efforts to translate the bible into English. A hundred years after Hus and Wycliffe, a monk named Martin Luther took up their arguments. This time, with the help of the printing press, a revolution began.

You may wonder why we are spending time on the reformation this fall, apart from the fact that it’s an anniversary year. Surely, enough has changed now that this history doesn’t have much to do with us. But I am struck by just how many issues of the Reformation we are still dealing with. What should the relationship be between religion and politics? How does new media change the world? And what is the Christian faith really about?

Beyond the issues which began it, the Reformation is also a case study in conflict. Through the course of the conflict, we see failures on every side to recognize who the church is called to be.

Standing where we are now in history, and as part of a Reform church tradition, we may describe the Reformation as a conflict between a corrupt Roman Catholic Church and a brave band of ideologically pure reformers. But it’s important to remember that the reformers were an integral part of the Roman Catholic Church themselves. They were priests, and monks, and everyday churchgoers. What happened 500 years ago was a family feud. It was a conflict within the church, which became a conflict within nations, which became an international conflict.

Probably, everyone felt that they were in the right. If they looked to Jesus’ instructions, I’m sure they felt that someone had sinned against them! Someone was speaking blasphemy, or leading believers astray, or suggesting radical redistribution of property, or threatening political overthrow. So it was only right that when a conversation of letters and councils failed to solve the issue, these members of the church resorted to separating from one another: with denunciations, and excommunications, and new church formations, and international relocations, and war.

But Jesus’ three great sentences about how to deal with a conflict don’t stand alone. They’re part of a broader message, even if you only read the chapter they are located in.

Jesus asks us to be honest about our disagreements, and to deal with them directly. If necessary, he tells us, we may separate from one another. Separation, however, is different from escalation, and it is different than violence. In the church, in our nation, in our world, Jesus calls us to treat one another as children of God; to avoid doing what would cause other people to stumble; to care for those who are most vulnerable; to forgive one another without limit. And wherever two or three gather in God’s name, as Jesus tells us at the end of the passage, God is with them: whether they are on what we choose to call “our side” or not.

This is a provocative message. It goes against all of our instincts. How can we simultaneously denounce anyone’s ideas and actions, as fundamentally dangerous to the sanctity of the church, or to the common good, or even to our own personal safety – and yet still keep in mind that this person is a child of God, worthy of care and forgiveness?

Try, for a moment, to imagine a person in today’s world towards whom you have a righteous anger. Hold in your mind a person who you believe has spoken or acted in a way that defies God, endangers community, or maybe even threatens your welfare or the welfare of those you love. This person may never listen to your truth, no matter how many witnesses you bring along with you. You may need to separate yourself, protect yourself against, this person, and their actions. And yet, try to hold in your mind at the same time, the idea that God loves them, and includes them in God’s embrace, even when you cannot.

The Reformation, as it splintered the western church, made important changes that opened up the Christian faith to so many. Many conflicts today also have noble ends: for example, to release our country from the bondage of white supremacy, anti-semitism, homophobia. Jesus calls us to struggle on towards love and justice. And Jesus also call us to keep in mind that we are fundamentally one with our enemies. Our welfare depends on one another. We belong to each other, across divisions of church, politics, ideology, and geography. Despite our division, God is drawing us together, towards a future unity that we cannot yet imagine. Thanks be to God.