Luke 24:13-35

It’s the third Sunday of Easter. Maybe it feels like we should be farther along in the story by now. Maybe it feels like everyone should have already adjusted to the news of Jesus’ death and resurrection. But on this third Sunday of Easter, we receive a story from the Gospel of Luke in which it’s only hours since the empty tomb was discovered. We’re still in the very first day of Easter.

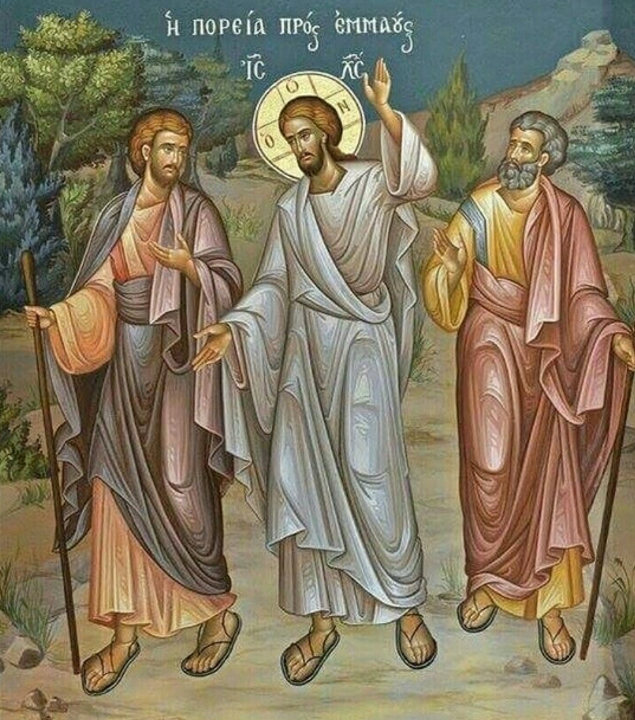

Two of Jesus’ followers are walking seven miles from Jerusalem to Emmaus. We don’t know why they go. While they walk, they discuss the troubling events of holy week. And then, miraculously, Jesus comes to join them.

For some reason, these apostles can’t recognize Jesus. And when this stranger asks what they are discussing, they hesitate: standing still, looking sad. But like most of us, they are grateful to find someone who is honestly curious, someone who will wait for an answer, someone who will really listen. So they tell this stranger how Jesus, a prophet mighty in deed and word, was handed over and crucified. “But we had hoped,” they say, “that he was the one to redeem Israel.”

But we had hoped! All of us know this feeling; the strange sense of disjointed surprise or disbelief that comes upon us after accident, illness, tragedy, pandemic. We had hoped, perhaps, for a miracle; or we had planned for a special event; or we had simply expected that life would go on as usual. But we had hoped, the apostles say, that he was the one to redeem Israel.

It’s painful to realize that you’re on an entirely different journey than the one you had hoped for, or planned for, or expected. Still, as one of my colleagues wrote this week, we have to travel the road we’re on, and not the one we wish we were on. We have to travel the road in front of us, not that other imagined, anticipated journey.

What would you tell Jesus – or anyone else who asked, and waited, and listened,– about the road you’re on today? If you had seven miles of slow travel, field and open sky around you, space and time and a compassionate ear? What would you say?

Some images of this story make me laugh. They may be beautiful, as this one certainly is. But it seems unbelievable that Cleopas and his companion do not recognize Jesus. The artists can’t help themselves; they make Jesus obvious to us. So it seems strange that the folks in the picture don’t get it. I want to say, Hey! He’s right there! Look at the halo! Check out the distinctive white robe!

But although many artists make Jesus beautifully obvious to us, I think many of us miss the holy encounters that we are a part of, at least in the moment when they are happening. Out of grief, or self-involvement, or practicality, we miss that there’s holy presence RIGHT THERE, beside us, in our most difficult moments, or in our everyday.

The two disciples do eventually recognize Jesus. It happens after that long walk, when he listens to them. It happens after he interprets the prophets and the scriptures for them, explaining the larger story that they’re living in. It happens when he blesses and breaks the bread at dinner that night; they know him in the breaking of the bread. Maybe there’s a reason that flour and yeast are hard to come by right now: something to touch, to taste; something that is real, and nourishing, like the presence of Christ.

Please pray with me: God, thank you for travelling with us, when things are not going as we had hoped, planned or expected; when we find ourselves on strange new roads. Thank you for listening to us, for as long as it takes, when our hearts are full of grief. Thank you for feeding us, with prophecy and presence, with bread and blessings. Amen.